One Battle After Another

A discussion covering the technical details of the film’s VistaVision film production, the importance of creating dynamics, and the calibration of tone.

Today on Art of the Cut, we speak with three members of the post team for Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, One Battle After Another. Joining us are editor Andy Jurgensen, associate editor, Jay Trautman, and film assistant editor, Andrew Blustain.

The film was shot in two different film formats including VistaVision and the film was finished in a variety of formats, leading to a complicated and fascinating post process.

Andy Jurgensen has been on Art of the Cut before for another Paul Thomas Anderson film, Licorice Pizza, for which he was nominated for a BAFTA and an ACE Eddie.

Andy was also an assistant editor on Phantom Thread, Bombshell, Trumbo, and Inherent Vice.

Jay Trautman was a visual effects assistant editor on Dune 2, an assistant editor on Oppenheimer, first assistant editor on Licorice Pizza, and was an assistant editor on The Book of Boba Fett, Grey’s Anatomy, and House of Card

Andrew Blustain was an assistant editor on Tenet, visual effects assistant editor on Dunkirk, an assistant editor on Oppenheimer, and second assistant editor (film) on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

The movie was inspired by a novel by Thomas Pynchon called, Vineland. Did you read that?

JURGENSEN: It wasn’t written on the script that it was inspired by or based on anything. As the shoot was going on we were hearing rumblings that there were similarities, but it wasn’t something that Paul asked me to read. It wasn’t part of our research.

TRAUTMAN: I had read it many years ago, but it seemed to be all original. It had echoes of the story. But no, it wasn’t something that we were looking at.

JURGENSEN: And I didn’t want to read it, unless Paul had asked me to. I wanted to treat the movie as its own thing and stay objective.

Andy, this was your second film with Paul Thomas Anderson with you as the editor, plus two others that you did as an assistant editor. How has that relationship evolved?

JURGENSEN: I started on Inherent Vice as an assistant. I guess that was 2013. So it’s just evolved. Paul likes to use a lot of the same people in his crew. It’s like a family.

I was lucky enough to be brought onto that project and lucky enough to continue on as an assistant on Phantom Thread.

I worked as an editor on a bunch of his music videos. There’s a trust there – learning Paul sensibilities, learning how he likes to work. There are a lot of specialized things that we do on his movies: cutting negative and making film prints and doing dailies. I’m used to that process now.

I was lucky enough to be bumped up to editor on the last movie, Licorice Pizza, and it went well. I think it just evolved to working on this movie.

I was looking back at my calendar this morning. We were doing camera tests for this movie back in the summer of 2023. That was our first test with the VistaVision cameras and the look of the movie. So we’ve been working on this for a while.

With some of those specialized ways Paul works, how does that affect what you’re doing as an assistant or associate editor to cope with those methods?

TRAUTMAN: It starts right away with dailies, because Paul likes to screen film print dailies at the end of the day or the beginning of the next day, whenever they can get printed and back to the set.

So a lot of what Andy and I are doing during production is preparing for those dailies screenings. It’s much more focused on that than sort of a normal assistant editing job where I would be preparing Avid bins for the editor to be cutting every day.

We’re much more focused on making sure the dailies get screened on film, the film looks the way it’s supposed to look, and that everything got through the lab.

Then we don’t even make the Avid editing material until after that’s screened and Andy looks at the color.

We make sure that the dailies colorist got it to look the way Paul wants it to look, and Andy works with the lab to make sure that the Avid media matches the print as closely as we can.

So really, production is a totally different thing than on most jobs that I do.

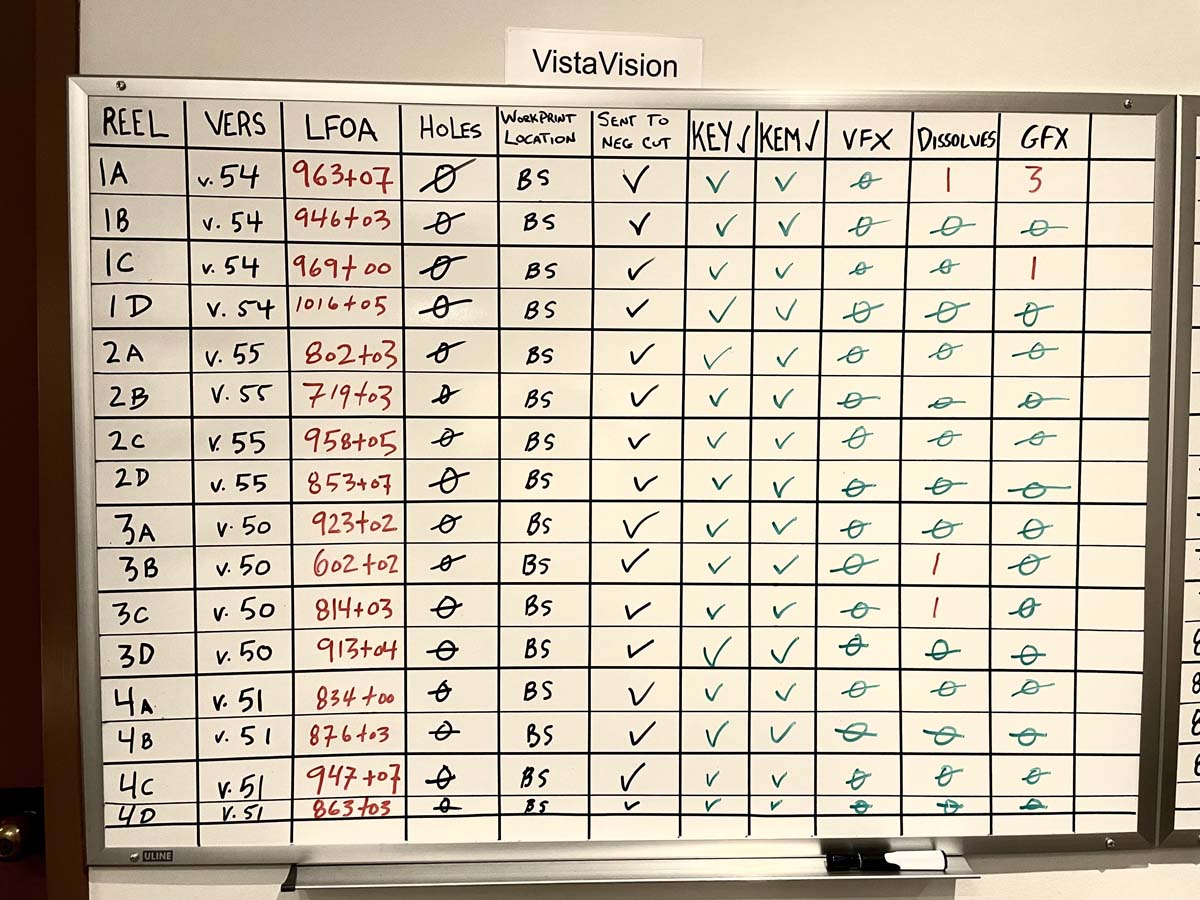

BLUSTAIN: I came on after production wrapped, for the conform. We were working with two different film formats: the eight-perf VistaVision and the four-perf Super 35. Because we had two different formats, we had two different sets of conformed work picture reels: one for the eight-perf and one for the four-perf.

During the course of any given reel - because we would cut back and forth between the two formats - we would put in a slug as a placeholder to denote where the alternate format footage would be.

So that was kind of different. Some things were just like any other show with pull and change lists that Jay would generate for me out of the Avid (as in a normal workflow) save for the two formats, of course.

And that was a constant set of revision and changing as Andy and Paul would recut and then once the reels were locked, we marked up the work picture for the negative cut and sent them to the lab.

But in terms of working with Paul, he worked at a separate location with Andy, so I personally didn’t get a lot of one-on-one interaction with him until we got to some of the timing sessions and work picture screenings.

I want to talk a little bit about some of the editing. One of the things when you’re editing a film like this: sure, the pace inside of a scene is important, but also the pace of the overall film is important. I was interested in finding out whether you felt like you needed to get to a certain point in the story quicker or slower - like the birth of Willa or Willa becoming 16 years old, or any of those other milestones?

JURGENSEN: Definitely. This movie is relentless in a way. So much happens throughout - even just in that prologue. But then once you hit the end of that prologue, you go off in another direction and it’s a whole other movie, basically.

We were very aware of the length of the prologue. It’s tough because you don’t want it to be too short or it won’t be impactful. The actress that plays Perfidia is so great, and she’s really only in the prologue, so you want to make sure that her character is established.

As the movie is going on, there are these peaks and valleys. It’s those Christmas Adventurer scenes (the story of the antagonists) that give you those moments - those valleys - where you can kind of breathe a little bit.

The shots are very stable. A lot of them are played in close up. Usually there’s not music or anything going on. It allows us to have these moments where the audience can take a breath.

So as we were building the movie and screening it, we were always aware of the pace and what we may need to cut out so that we could get to a moment of breathing and some comic relief faster.

It’s really the kind of thing where you have to just watch the whole movie and get a feeling that a section is working.

For example, the area that went through the most revisions was the DNA test sequence and everything that happens at the Sisters of the Brave Beaver. Again, you want tension, but you also want there to be some comic relief. You want there to be a bit of a “valley” before we get it into the final chase sequence. It took a little while to get it perfect.

Editor Andy Jurgensen

What were some of the creative discussions around trying to perfect that section? Trying to keep it moving along or was it more tonal?

JURGENSEN: What’s interesting is we actually didn’t always have the scene between Deandra and Danvers, the military guy who’s interrogating Deandra, in the cut.

We were able to use that scene to cut away from Willa and Lockjaw waiting for the DNA test to be done. Intercutting with that scene unlocked something there, because we could skip time a little bit.

We actually reordered a bunch of the lines in the DNA scene, taken from totally different parts of where they originally were in the script and how it was shot.

When Willa makes that comment about his shirt being too tight, there’s that laughter. The audience needs a joke there because it’s so tense. It’s just threading that needle of where you have the laughs and where you have the tension and not overstaying your welcome too long and then getting to the end of the scene and on to the rest of the movie: the chase.

TRAUTMAN: Initially, didn’t Lockjaw say, “It’s going to take 20 minutes”? Then that scene – without intercutting - really was 20 minutes long?

JURGENSEN: Yeah. And you don’t want it to telegraph to the audience: “Oh gosh, we’re going to be sitting here in this scene for 20 minutes,” so we had to take that out.

TRAUTMAN: And you were able to cut it down quite a bit and sharpen it. There were different emotional journeys with Willa and Lockjaw than where you ended up.

Do you remember any of the creative reasons or story reasons why you would have juggled lines around from that scene?

JURGENSEN: We just had to try stuff. We had tried it as scripted and it was feeling long and it just didn’t feel right, so then you basically target: What are the lines that we want her to say?

“Did you love her?” “Did you rape her?” And him asking about her father. It’s those things.

Willa and Lockjaw are both sitting in their own areas, so you can cut back and forth to close-ups even if the lines are completely out of order from how they were shot. We just were able to find good performances and make it work.

We really just had to distill it down to: What are the core lines? What are the best lines? And then figure out how to make the scene work.

TRAUTMAN: There is a calibration of Lockjaw trying on being a father and sort of asking her fatherly kind of questions and how she was responding to that - either making him more sinister or more empathetic. You sort of push that both directions and settle in a place where it works.

JURGENSEN: The Lockjaw character is very larger than life, so we tried stuff that was even more over the top, and it just was a little too much. You really have to make sure you gauge it so that it seems still somewhat grounded in reality. We definitely experimented with that section a lot.

I want to jump back earlier in the movie. After Perfidia gives birth to Willa there’s a scene where Perfidia jealously narrates about Bob’s affection towards the baby while we see him being affectionate and fatherly. Was that planned as narration, or was it actually two different scenes that you intercut?

JURGENSEN: There’s a scene where he is listening to Perfidia through the door and in that scene she did a lot of improvising. There was a lot of really good stuff in there, so we ended up pre-lapping a bunch of those lines over where she’s sitting on the couch looking at him rocking the baby.

I don’t believe it was really scripted specifically like that. Paul does like to pivot on the day and say, “Maybe we should try some things - try some different shots - let’s just see what happens” knowing that some of it won’t be used.

So I think that it was maybe an experiment when she was sitting on the couch looking at him, rocking the baby. It just ended up being a very impactful moment.

TRAUTMAN: Sometimes with his scripts, it’ll just say something like: PERFIDIA WATCHES PAT HOLD THE BABY or something like that, and you don’t know what that’s going to be until the footage comes in, because he’s writing and directing. Sometimes he just puts in a little note for himself and doesn’t flesh out the scene. Then we find out what that means when we see the footage.

JURGENSEN: He really wants to get feedback from the actors of how they’re feeling. Wants to involve the actors in how a scene might play out. It really helps the performances.

Is that difficult to edit that way because you’re not getting something that was written in the script necessarily.

JURGENSEN:Not really. I mean, with Paul, things evolve. He’ll shoot alternate versions of a scene.

Kind of going back to the dailies discussion that Jay was talking about, I’m on location with the crew. I am there with Paul as we’re watching the dailies at the end of each night projected on a big screen. Paul is playing music - either songs or score that Jonny Greenwood, the composer, has sent.

We’re experiencing the footage and that will spark another idea for Paul to say, “Maybe let’s reshoot this at a table instead.”

Things sort of evolve, and I’m part of the discussion. He knows that if we end up cutting this other thing out, we have an alt version where we can still get to the meat of the scene some other way. We just cover ourselves with different versions.

TRAUTMAN: The lined script becomes much less of a roadmap than the notes that Andy’s taking during the dailies screening process. We’re not off on our own blindly putting together a scene without knowing what the director’s thinking.

So many of the older editors that I’ve interviewed who screened dailies back in the day where you’re screening with the cinematographer and the director and other crew, say that they miss that so much. Tell me a little bit about the value that you see in doing that.

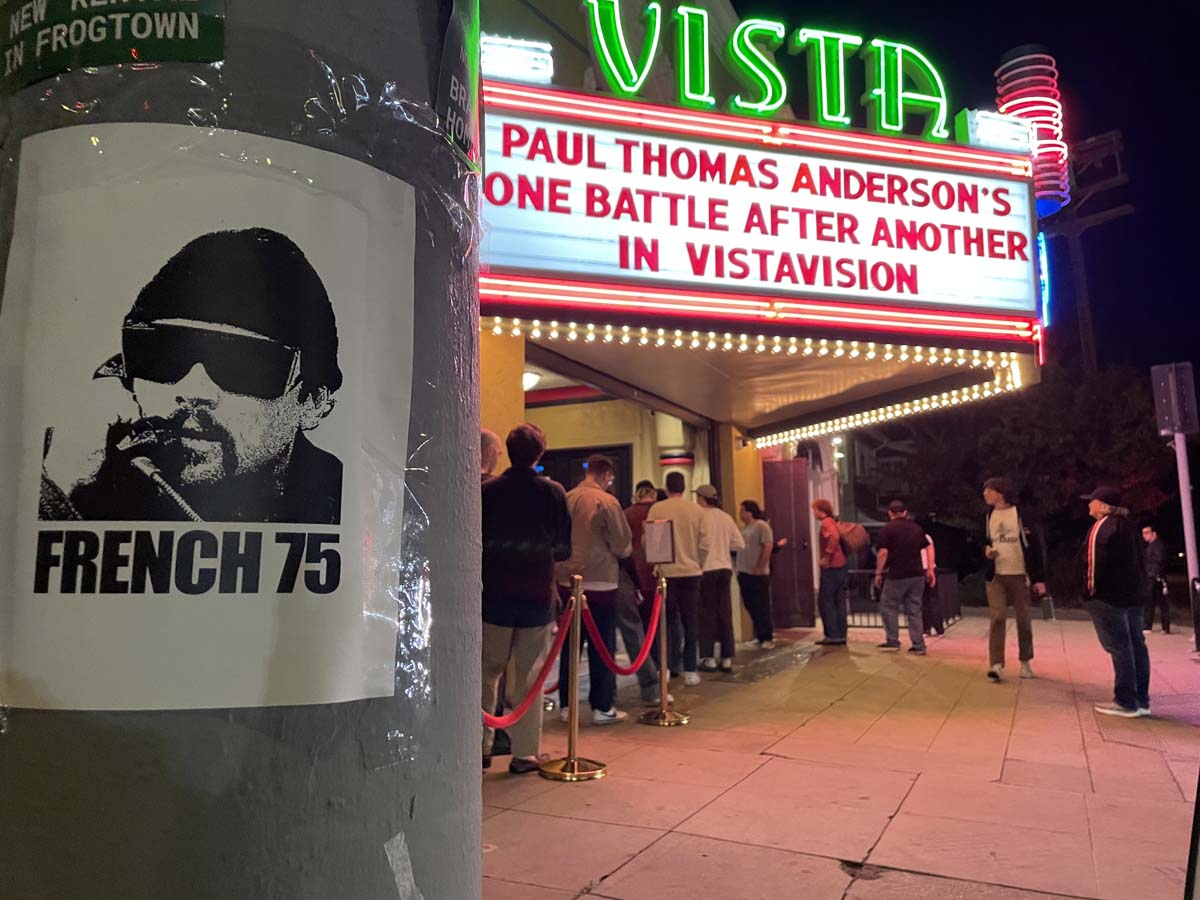

One Battle After Another post crew at the premiere

JURGENSEN: Having a communal screening of dailies does so much. First for the technical side - because you are checking the cinematography and the focus.

Since we’re shooting on VistaVision, which is a format that hasn’t been used in a long time, there were technical things happening with the camera or flickering – all sorts of things.

But seeing dailies on a big screen in a communal room, it gives you that experience of seeing facial expressions big, seeing all the little details.

This is a very funny movie, so watching dailies together can tell us when jokes are landing. What are we getting out of certain performances?

It just gives us that confidence that we’ve got the scene. It gives the actors and Paul and some of the other department heads, the confidence that it’s working. “Job well done. Now let’s go for the next day.”

We have some very small intimate scenes. But we also have these car chases. We had to see that stuff big to see whether it was impactful and working.

It’s the best thing that Paul does in the entire process. It’s so valuable and he’s never going to change his ways. It’s always going to be like this.

VistVision Projector

Do you have an assistant editor who’s there with you to take notes, or are you taking notes?

JURGENSEN: No, I’m taking notes. Jay was back in LA. We also had Colleen Murphy, who started out as a PA, then became one of our other assistant editors.

We also had a projectionist, Richard De Armas, who was carting around a Vistavision projector to all of our locations. We’d set up a screening room and we’d get the prints delivered each day by a driver.

I have a big binder that I carry with me. Jay will send a dailies template that lists all the setups and takes and which ones are the selects. I will choose from that which takes we’re going to watch that day.

And during the day, when they’re shooting, I will mark up and organize the digital dailies in the Avid. Then I’ll just start making string outs and assembling scenes and start putting it together.

Paul doesn’t want to see edited scenes immediately. Unless it’s something that we are worried about, he’s not wanting to see complete cuts every week with temp music and sound effects.

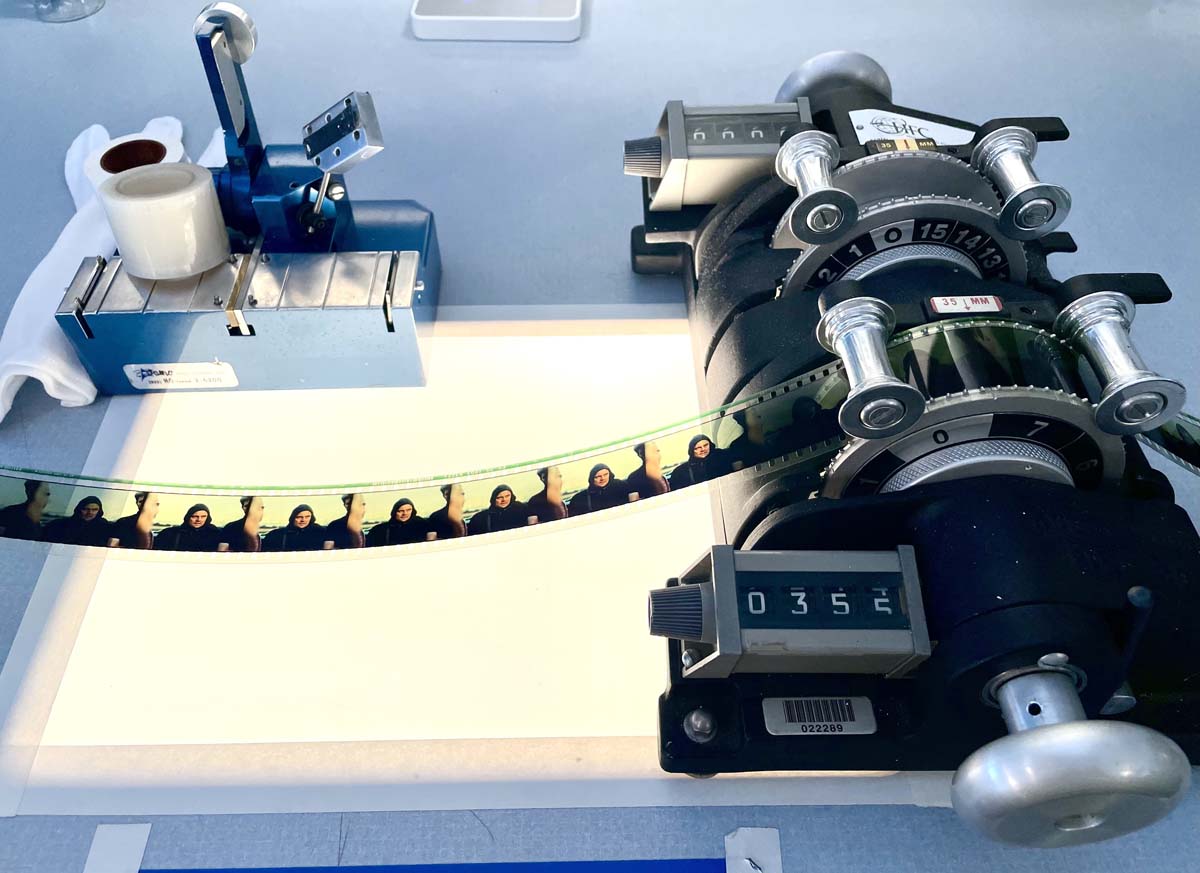

Workprint on the KEM

Andy, you mentioned this eight-perf and four-perf difference and what you were doing on the film, what are the technical aspects of that and how you had to work on the film?

BLUSTAIN: Both formats - the eight-perf VistaVision and four-perf Super 35 – are both printed on 35mm stock, so it’s not that we need special equipment for each format, save for an eight-perf sync block on the bench, and a VistaVision eight-perf KEM connected to a DV-40 player that we used to check the sync on a reel when the changes were done.

We also had a 35 four-plate to check the sync on the Super 35 reels as well. The biggest challenge was they’re both printed on 35mm stock, but they’re both running at 24 frames a second. VistaVision - because the frame size is larger, horizontal and twice as big - runs at eight frames a foot, as opposed to the normal 16 frames a foot that the Super 35 runs at.

As a consequence, for a given amount of screen time, you’ll have twice the amount of VistaVision footage running through the projector as you would with regular four-perf.

So Andy and Paul and Jay had to keep this in mind, and we would calculate the Super 35 sections that would eventually be filmed out and printed into eight-perf. We would have to think, “Okay, this section is 70ft in Super 35, but it’s going to be 140ft in VistaVision.” So you’re always doubling the footage.

And those calculations had to be carefully factored in by Andy and Paul when they were editing and deciding where the reel breaks would be.

For somebody that might not be familiar with this process. Andy was cutting in Avid, then what was he delivering to you to be able to conform this on the film side

BLUSTAIN: Jay would output lists from the Avid for me, whether it was “I’ve got some eight-perf list for you” or “I’ve got some four-perf lists for you.”

Though it’s not common anymore, it followed a normal work picture conform workflow. I would just switch back and forth depending on the format: “Let’s get the four-perf synchronizer. Let’s get the eight-perf synchronizer.”

So it was pretty straightforward. There was a lot of technical challenges, but I was really surprised at how straightforward and simple and bug-free the whole process has been.

JURGENSEN: We should really call out FotoKem because they were the ones that really did such a good job printing our dailies and release prints.

They bent over backwards to convert a laser film recorder to the VistaVision format so that we could film-out certain sections.

They had to get a Vistavision projector up and running at FotoKem so we could do the color timing. Then they also blew up the film to 70mm. FotoKem and our Post Supervisor Erica Frauman were working hard for years to make this happen and we could not have done it without them.

I want to get it back to some of the editing challenges. Structurally, there are a few scenes that - at least into my mind - could have gone anywhere. One of them that I’m thinking of is the Christmas hymn when Tim Smith shows up at the house. That didn’t have to go right there. It’s not chronologically linked to scenes before it or after it. Talk to me about deciding where those kinds of scenes went, and did they usually just go where they were scripted?

Workprint on racks… it looks a lot different when it’s not on a hard drive.

JURGENSEN: I think that goes back to my previous point about the peaks and valleys, because prior to that scene, we have just followed Bob and Sensei driving the car through the riots, into the perfume shop, upstairs on the phone, then Bob going up to the rooftop. It’s like a 25-minute sequence underscored with 25 minutes of Jonny’s score.

After he falls on the ground, the audience needs a release. We transition to the Sisters of the Brave Beaver so we can get Deandra and Willa to their destination and Willa into her bedroom.

But at that point, we go to Tim Smith and the second Christmas Adventurers scene. I don’t quite remember the script - if it was supposed to be there or not - but, it just felt like a good moment to breathe.

There’s a scene where Bob gives Willa the letter from her mom, which is intercut with the disposal of a body – not to do a spoiler alert… Were they scripted as intercut? Did you find that there was some reason why that body disposal or the letter reading needed to be intercut?

JURGENSEN: It wasn’t scripted that way. Originally, we were following just one side of it fully, then the other. We screened it like that for a long time.

The body disposal scene used to play completely dry, so when we moved up that really sweet music cue that plays over the scene when she reads the letter, it sparked something. We decided to see what would happen if we intercut Bob’s kitchen table speech with the body disposal. I think it makes a nice juxtaposition.

On one side - the side of the oppressor - and the other side, a family unit – which has more of a hopeful tone to it.

So I think it’s the combination of the music and seeing the resolution of these two storylines side by side.

TRAUTMAN:It also brings Perfidia back into it because the story really starts with this triangle between the two men and Perfidia and it shows what side she’s chosen as the father figure.

Board with workprint into

Needle drops. You talked about music a little bit. How many of the needle drops were scripted? How many of them got found by the editorial team or the music supervisor and how much did they change?

JURGENSEN: The Steely Dan song was always in there at the beginning. In fact, even when we were screening dailies of that scene, Paul was playing that song.

We wanted an epic ending to the prologue and then begin the next section with Steely Dan to show the difference 16 years later.

Then the Jackson 5’s “Ready or Not” - he was playing with that a little bit during dailies, but we didn’t really know where we were going to put it.

I do remember the day that we were working on the scene when Bob leaves the hospital and escapes. We tried that song there and I think both of us got a smile on our face. It just felt right.

It’s fun watching screenings and seeing people perk up at that part because it really launches you into the last third of the movie.

That’s another big point with something like a needle drop is the kind of energy it can inject into the film at a point where it needs air, because right before that’s really tense and difficult.

One Battle After Another film cutting room

JURGENSEN:Yes, we’ve just had the second Christmas Adventurers scene and then we go back to the Sisters of the Brave Beaver where Willa’s shooting the machine gun and talking to Deandra, asking whether her mom is a rat.

Next, we go to Bob and get the big reveal of Sensei in the car down below. It just feels right to have a great song there.

TRAUTMAN: Andy mentioned that Paul plays music during dailies. He always has a playlist that is shared with me, and so I’m just trying to collect all the stuff that’s added to that playlist and get it into the Avid so that when they start cutting, we’ll have it.

But Paul’s so into music that he knows what he wants and we’re probably not going to find something that he hasn’t thought of to pitch to him.

And how are you organizing all those needle drops, if they don’t have a specific place to go, for example, like this Jackson Five song?

TRAUTMAN: We just have a bin of “Paul music” that we add stuff to, then it goes from there.

JURGENSEN: Paul can be sometimes a little impatient with me cutting a song in and he’ll say, “Just play the scene” and he’ll pull up the song on his phone and just start playing it.

We watch the movie off the Avid on a big projector and a really nice sound system. So he can just be sitting on the couch and I’ll hit play and he’ll plug his phone into the speakers, or he’ll just put it up to his ear and audition stuff.

TRAUTMAN: That brings up another point about the way we work in the Avid. We work with ‘Direct Out’, so we have our tracks going into a mixing board, and we send the dialog, the effects and the music to different channels on the mixing board so Andy can just mute the music on the mixing board if Paul wants to play other music from his phone to audition. It makes it easier to just not have to do anything in the Avid.

VistaVision screening at the Vista

JURGENSEN: And we also have screenings in this room, so let’s say if the sound mix isn’t perfect yet – the music is maybe a little too quiet – Paul can boost the music level live on the mixing board while the movie is playing. Or he can adjust levels for the sound effects channels.

Later, I can actually do the adjustments for real in the Avid with rubber-banding.

There were a couple of places where I felt like the volume of the music or the volume of the sound, the dialog, was used almost as a tool. Loudness as an editorial tool.

JURGENSEN:It’s just creating these peaks and valleys, just in a different way – audibly. Paul’s always talking about dynamics, “How can we make this more dynamic in either the camera movement or the way things are edited or with the sound?”

At the beginning of the movie there’s that really big, loud orchestra sound. So we always wanted to have a really strong first note at the beginning of the movie.

We also have that same loud orchestral piece play after the first Christmas Adventurers scene when Lockjaw walking down the hallway, and then we play it again when Willa and Lockjaw meet before the DNA test and are looking at each other in profile.

There were motifs of these really strong chords at important parts of the movie.

VistaVision workprint bench

Another audible example I can think of is in the final chase scene. About halfway through what we call the “River of hills” sequence, Willa’s looking at the rearview mirror, and she’s looking at bits of the road in front of her.

We dropped out the car sound there, and we’re playing up the beats in the music and we’re just hearing these whoosh sounds.

Then when she looks in the rearview mirror and sees her pursuer, we ramp the car revs back up again to have that dynamic impact. Our sound team is great - headed by Christopher Scarabosio, supervising sound editor and one of our mixers. He’s worked with Paul for years and years.

Tell me about score a little bit and how you temped or was the composer giving you stuff throughout? How did that work?

JURGENSEN: The composer, Jonny Greenwood, was giving us stuff throughout. In fact, even during dailies, he was sending ideas to Paul’s phone. They’re not necessarily written to specific scenes. Paul would sometimes play those cues as we’re watching dailies.

Then there was a point in which we did send a really long cut to Jonny. He watched that and played with that. For the big “Baktan Cross” section where the piano piece is playing for 25 minutes, I think Jonny initially sent us something that was maybe ten minutes long. I cut it up and laid it across the entire sequence, moving around some of the ups and downs and more quiet parts of it. I did a rough music edit which we sent to him and Jonny cleaned up.

For the later part of that cue when it ramps up, he layered on even more instruments. So it’s constantly evolving. But we really didn’t use that much temp music on this movie. It was mostly just using what Jonny sent.

Jay, can you describe how you organized this music?

TRAUTMAN:It always went to Paul first. He would audition a lot of these ideas from Jonny, and it would only ever make its way to the Avid if it was something that he was interested in really using on a temporary basis.

So we didn’t have an overwhelming amount of material in the Avid from him, and so we would tend to organize it just by when it was sent to us.

What about music-less scenes? There were several of those. Was that just part of the dynamism? Or why were you choosing specific scenes to play without music - to play dry?

JURGENSEN: Definitely it was part of the dynamic nature – the peaks and valleys. For instance, the scene in the prologue where Profidia is leaving Bob and the baby, she has this monologue where she’s talking about why she’s doing it.

There was score underneath that scene at one point, and it just didn’t feel right. It was maybe pushing it too hard, so by playing it dry, it just makes it more real.

Also, the first car chase after the bank robbery, we didn’t do any music for that. We were trying to go for a ‘French Connection’ thing there, so its about following the car and letting the soundscape be more about the metal crunching and the revs and crashes and the helicopter sounds.

The Christmas Adventurer scenes, as I’ve said, gives the audience a second to breathe. So playing them dry and letting these creeps do their lines, it makes it more effective.

The reason why those scenes work so well and why they’re funny, is that those actors are committing 100% to those lines. They’re not hamming it up. It just works better to have it dry.

Speaking of tone, let’s discuss determining or balancing the seriousness of the topic and the peril with the comedy elements. Were there things that had to go just because the tone of it didn’t set right in the place that you were working?

JURGENSEN: It really always was sort of a balancing act. We always were aware of not being too preachy. We don’t want to be too political. The message of the movie is more effective because we are making light of certain things. It could have definitely been a different kind of movie if it was fully serious.

Andy, anything else that people would be interested in about how the film part of this all worked?

BLUSTAIN: One of the really fun things that happened - actually quite recently, because it was at the end of the process - is when we finally had a complete VistaVision print, and we showed it at the Ross Theater on the Warner Brothers lot, and we plattered it.

At some point someone said “This has never been done before.” Back in the day when VistaVision was coming in the 50s, it was done with change-over reels. It was the normal way of theatrical presentation. But a VistaVision print had never been plattered! That was a really exciting moment.

Can you explain what it means to platter?

BLUSTAIN: Plattering the film as opposed to having reel changes where reel one is on Projector A, and reel two is on projector B, and it goes back and forth.

Instead, you take all the reels and you make a giant reel and put it on a horizontal platter that feeds from the platter over rollers to the projector and then takes up on a separate platter underneath. It’s usually this giant three level platter set up.

So what it basically means is that there are no changeovers of reels, there’s no changeover marks, there’s no projectionist getting it wrong. It’s a smooth transition. Basically, the whole two hours and 40 minutes is in one seamless reel.

JURGENSEN: For me, this is the first movie I’ve worked on with so many different versions. We have the digital version, which includes regular, DolbyVision and IMAX (with different aspect ratios). We also have 70 millimeter IMAX, which is the full 1:43 size.

We have regular 70mm, which is 1:85:1 pillar boxed. We have the VistaVision prints. We’re maybe making 35-millimeter prints.

We’re doing 4DX, which is the moving seats. There are so many ways in which you can experience this movie.

TRAUTMAN: Just along the lines of what we were just talking about regarding all the different formats. Andy mentioned starting to do camera tests for the VisionVision cameras more than two years ago.

The camera was a big part of it, but we were also figuring out how we were going to be able to finish the film. Along with FotoKem and Erica Frauman, our post supervisor, we did a lot, a lot of testing. Can we convert VistaVision optically into 70mm or is our hero format going to be 70 millimeter?

Are we going to optically blow it up to IMAX? Are we going to take our visual effects and film them out to IMAX, then optically reduce them to VistaVision?

Nobody has tried to finish a film in VistaVision in a really long time, at least since digital visual effects are possible. We finally got there, and it’s a whole other podcast to talk about all the steps, but it is a very, very long, complicated thing.

When we talk about it here, it doesn’t quite do justice to all the hard work that everybody put in to make it happen.

Thank you so much for talking to us.

JURGENSEN: Thank you, Steve

BLUSTAIN: Thank you so much.

TRAUTMAN: Yeah. Thanks, Steve.