Spinal Tap II: The End Continues

Discover the editor’s collaboration process with director Rob Reiner, how they used a synced recording of an audience screening to refine comic pacing, and why fantastic comic moments get deleted.

Today on Art of the Cut, we speak with Bob Joyce about editing Spinal Tap II: The End Continues.

Bob’s been nominated for a Emmy and an ACE Eddie for editing Albert Brooks: Defending My Life. Among other films his other work includes two other Rob Reiner features, Shock and Awe, and LBJ.

Bob, it’s so nice to have you on the show. This must have been a fun project to work on.

I saw it in the original film, in the theater when I was 14 years old. I was already a film geek making Super8 films. And at the time I was also into Metallica and heavy metal music, so it was the perfect young movie for me.

I could tell right away that it was a mockumentary as opposed to some people. When it first came out, they thought it was real! [Director Rob Reiner] tells the story that when they first started screening it, people asked, “Why would you make a film about a band no one’s heard of…and one that’s so bad?”

I think that’s when he knew: “I think we got something here.” I saw it when it first came out so it was an honor to work on this film.

Would 14 year old Bob believe you if you told him, “Hey, you’re going to edit the next one?”

Absolutely not. Working with Rob - just being around the people in his orbit. The last film we did together was a documentary about Albert Brooks that was that’s on HBO: Defending My Life.

Just being able to work with Rob and Albert on that was fantastic, because I had grown up watching his films along with Spinal Tap. It’s just been a dream come true.

You worked on LBJ too.

Yes, so it’s been a long-standing relationship. I believe this is our fifth film together. We started working together in 2015: a small film called Love Being Charlie that Rob directed and his son co-wrote.

He couldn’t use his normal editor - Bob Layton, who he’d been using actually since Spinal Tap - because the budget was so small. We just got along great so we’ve been working together ever since.

Talk to me a little bit about the documentary style of it.

I approached this - as Rob did - like a real documentary. It was perfect that the previous film we’d done was the Albert Brooks documentary - which was a real documentary.

Rob had never done a real documentary, either so both of us were learning the process, so going from the Albert Brooks documentary right into this one was almost the perfect set up.

It’s more of that cinema verité sort of documentary style as opposed to the documentaries you see on Netflix these days.

One of the things that Rob told the DP - Lincoln Else - while shooting it was, “There’s nothing you can do or that’s wrong. If it’s out of focus, that’s okay.

If the camera’s bobbling or if you see the mic or that’s okay.” You sort of need to forget all the rules that you learned on a narrative film and say, “We can do anything we want with this.” That’s really how I approached it.

Screenshot of the Avid timeline for Spinal Tap II

Did you organize it more like a documentary or more like a feature film where there are slates with scenes and set-ups?

I sort of knew what Rob was going to do, but the crew had to learn. They thought, “Okay, this is going to be a normal film where we do a master shot, close-up…” It wasn’t anything like that. Rob would start talking, and sometimes they weren’t even rolling the camera yet.

So a lot of tail slates! Rob would shoot with two cameras and there was no script. I think there was an 8 to 10 page outline. That was it.

They sort of knew the beginning of the movie and the end of the movie, and everything else was what Rob called The Blob - which was the middle of the movie - was a sort of an unformed structure.

At first we tried to work on scenes as they came in, but Rob started to get frustrated. He said, “This is the wrong way to do this. Let’s just start from the beginning and as we edit the scenes, we’ll just see where it takes us.”

That was the best way to approach this. terms of

They shot with two cameras and sometimes Rob would do two takes. They would be 30 or 40 minute takes and the guys would just go. Sometimes Rob wouldn’t call cut. He would just walk into the room and say, “Okay, I think we got this.”

On the second take they might move the two cameras to different shots or different setups. I would edit those into a 30 minute scene.

It would be almost its own movie. You could watch that 30 minute scene and it would be great. Then Rob would come in and he would cut that down to about two minutes.

Paul McCartney, Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

I remember being a fan of Spinal Tap and being one of those people that buys all of the Criterion Collection releases every time they come out with a new one. I had the original Laserdisc. It had all 90 minutes of deleted scenes.

I would watch them and say, “How did they cut this out? Why did they? This is so great!” I learned very quickly that it’s all story. It may be the best joke in the movie, but if it doesn’t push the story forward? Get rid of it! That was amazing to me.

As you probably know: you fall in love with the scene and then maybe someone says, “We’ve got to lose that.” And you say, “We can’t lose that! That’ll ruin everything!” Then the next day you never miss it. You realize, “This works.”

Rob’s the master at that because he’s always thinking about the audience. Just tell the story. We would move scenes around. The middle of the movie was what took the longes - just creating a story from all of these improv scenes that they did.

I think we succeeded in finding a good story which is what you would do on a normal documentary. You have to find a plot or a structure. We knew the beginning, we knew the ending, but the middle was just: “Let’s see what happens.”

Let’s say Rob said, “You know what? We need some conflict. This is a point in the movie where the guys have to butt heads.” We would find something that may have been done later and put it up front just to sort of set up that conflict.

Rob always said, “It’s sort of like having all the puzzle pieces without the picture of the puzzle, and you’re just trying to find the story.”

That’s really what it is. Sometimes it can be frustrating because you think, “Where do we go next? What’s the next scene?” It’s funny when I watch the movie now, I think, “Well, this is the only way it could be told.”

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

As I was watching it there were some scenes where I felt, “This scene could be anywhere in the movie, like the merchandise scene. Talk to me about making those decisions. What were some of the creative discussions?

The biggest issue was that the guys hadn’t been together for a while, and you had to find that tension. So where are the scenes that have the tension?

Maybe there are places where they mentioned something that happened in the past or they allude to something.

So let’s set that up earlier in the film and then revisit it a couple times throughout. That would be something that we would need to set up.

It was mainly in the first act where you had to build the tension, then little things like Rob did an interview with Michael McKean where Rob says, “You guys seem to be gelling now” and I pick up on that and think, “I have to save that bit for later in the movie when they’re actually starting to gel.”

We had no plan where that would be. That was just part of an interview. But I thought, “After a great recording session or where they’re rehearsing and David St. Hubbins says something like, “You know, it’s pretty good. We’re getting there.” That’s where that quote goes.

It’s really like writing with pieces of film. That’s what you’re doing. Rob is a writer, so he’s always thinking about stuff like that. I don’t know if the guys have that in their head when they’re improvising or not.

Christopher Guest could never do a take twice because he doesn’t remember what he does. He can’t do it twice, so it was really just reminding myself constantly that this is sort of like a documentary.

I would create separate bins of rehearsal stuff or tension. I’d create my own little organization that would be different than any other film I’ve ever done, because there was no script, so it really was finding that that middle ground between a narrative film and a real documentary. I felt you had to approach it that way.

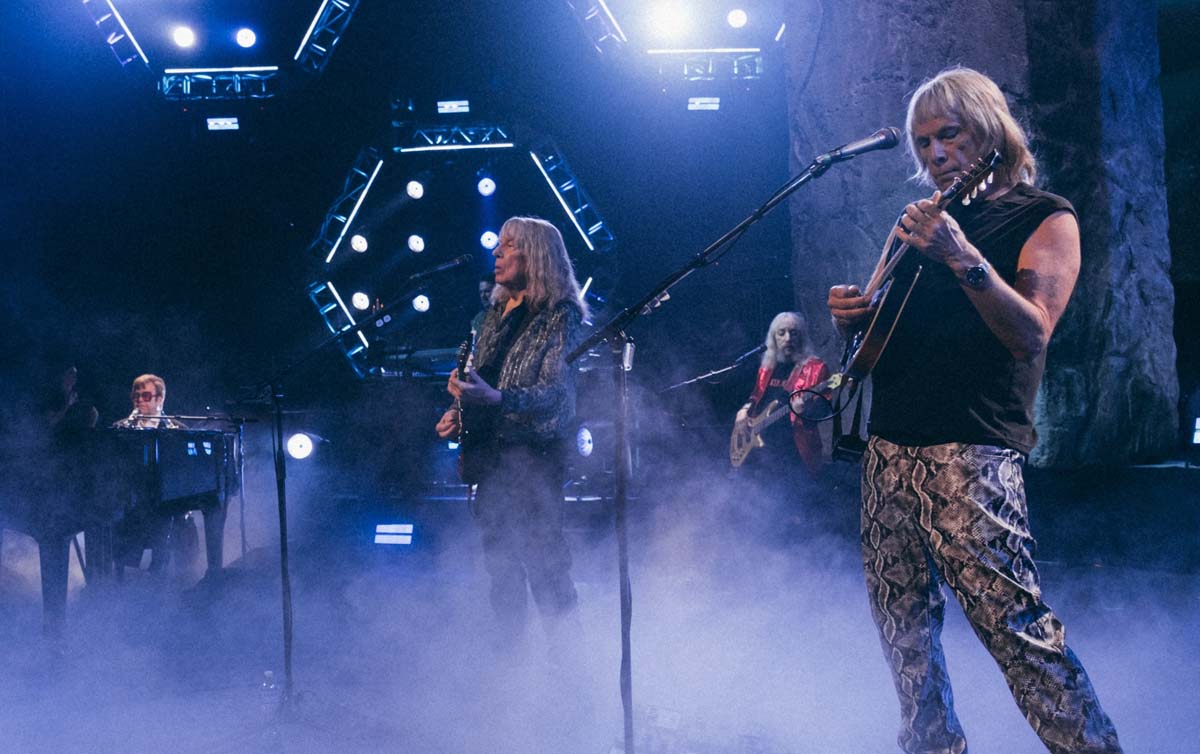

Chris Addison, Kerry Godliman, Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

Something like The Last Waltz where they were intercutting things with the music and rehearsals leading up to the concert. For example, the little scene where they’re trying on different potential outfits. They have a designer come in with some concepts for their costumes.

I’d have to think, “Where does this go?” I knew it needed to go near the end because it would be closer to the concert.

One of the things we came up with in, in the editing, was creating a ticking clock with the on-screen graphics that say: “One week to the show.” “Three days to the show.”

You’re giving the audience a timeline. We’re getting the audience excited as we build to that concert. I was always pushing for building the momentum towards the concert.

You want the audience to stay with you and get them excited about: I’ve got to see what happens! Looking back, my biggest thing was that we have to set that up.

Perhaps there’s different rehearsal studios. There’s the small rehearsal studio where they start rehearsing, and then they sort of get to a bigger space, which wasn’t necessarily meant to be later in the movie or earlier, but I felt: “We need to progress – to go from the smaller rehearsal stage to the bigger one, then to them at the venue rehearsing, so that’s sort of structured that way.

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

There are a couple of montages. I was thinking specifically about the drumming montage.

That’s a great montage for anybody that’s a Spinal Tap tap fan, because you understand the point of it. It’s a 41 year old running gag: the drummers they’ve lost in mysterious ways. But that was a tough scene to cut because it’s an audition sequence.

The idea is that they’re not telling these people they’re auditioning for Spinal Tap. It’s a secret gig because otherwise people won’t want to audition for a band whose drummers regularly die. Each drummer would perform the full song. We had to intercut them each only doing part of the song.

For that scene, I had to tell Rob, “Just leave me alone for two days. Let me just play with this.” Then he would come in and say, “More of that. Let’s get rid of that.

That person doesn’t work.” Then cutting to the reactions of the Spinal Tap guys to establish that they weren’t that crazy about everyone.

The hardest part of that was the music editing: trying to make it flow as one piece of music because they were playing to a backing track.

There are some unconventional drummers in the piece, so that made it fun. That scene took a little bit longer than most of the scenes just because of getting the music right. Usually I cut to music, even if it’s just my own temp score, to give me a rhythm. In this case, I had a song, so it made it a lot easier.

My recollection of watching the movie was that the backing track was pretty low.

It was playing low in the room, so it was just the audio we had. We adjusted in the mix, but they were micing the actual drummers and they had a playback track. I would take the actual track of the music and sync that up, and I’d use that to cut to.

Obviously it’s a longer song, so I had to make some edits in it. Yes, it was mixed fairly low. It’s one of their well-known songs:” Tonight I’m Going to Rock You Tonight.” So basically it was a track that they had pre-mixed.

It was almost like a real audition, so I just used what they had in the room. I would try to use as much of the ambient sound as possible, because that felt more real.

I think the hardest part of that sequence was finding the right reactions from the guys. If it’s a goofy drummer, Michael just staring might be funny because it’s like, “What am I looking at?”

Or especially Harry Shearer! You couldn’t miss with a reaction shot to Harry because even if he’s just staring at the camera it was funny.

There are a couple of famous musicians that are part of the mockumentary. During one of them - Elton John - you intercut between the performance and interviews.

Marty DeBergi - the “director” of the film - does a traditional sit-down interview with Elton, which was, pretty straightforward, but then they rehearse the whole song straight through. I realized I can’t play through the whole song, so I started to intercut the Elton interview.

Elton - not even trying to be funny, just straight – says, “Oh, I love these guys! They’re great performers. They’re great musicians!”

So I thought, “This will be great to dip in and out of that interview rather than show the whole performance.

I thought it was a great way to trim the song down. It gave us a way to get in and out of it and get to the ending pretty quick.

I just experimented while I was doing my cut and Rob would say, “This is good. This is working.” Then he’d say, “Let’s cut it down a little more. Go to that. We don’t need that.”

Sometimes I’d think, “We can’t cut that!” But he’d say, “No. We don’t need it, and we don’t need that other thing either.” At the end of the day, he’s absolutely right because it’s tight. We don’t want to bore the audience.

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Rob Reiner, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

Talk to me about editing for a director who’s in the movie. I’ve actually edited a couple of times for directors that are stars in the movie. Talk to me about the difficulties of that. You’re in the editing room and you have to say, “I’m not sure if I buy your performance here.”

I did a film with Rob in 2018 called Shock and Awe. Before they started filming that film, one of the actors dropped out. They had to start shooting the next Monday. They didn’t have time to recast, so Rob - being an actor – decided to do the part.

That was in a very dramatic film. Rob told me that he really learned editing sitting in the control room of All in the Family, sitting behind the director and the technical director. It’s funny because sometimes I’ll be sitting with Rob and he’ll be saying, “Cut!” the same way you would in a control room directing multi-cam.

But he can separate himself completely. In that film I thought it would be a problem. But Rob would talk about his own character in the third person.

He’d say, “Cut away from that guy.” or “We need a better take on [his character’s name].” He’s not precious about anything. He leaves his ego at the door.

I know he doesn’t particularly love directing and acting in a scene because he likes to be able to watch the monitor. Rob knows what he wants when he’s shooting. He doesn’t really even do a playback. He watches it live when they’re shooting it and he says, “We’ve got this. Move on.”

Whereas if he’s in the scene, he’s got to go back and watch it. That can add half a day to the shooting schedule. But he treats his character like any other character in the movie. I don’t know what it’s like with other filmmakers.

They may be a little more sensitive about that, but I think that just comes from him being an actor for so long. His character is part of the story, and if it doesn’t work for the story, it’s gone.

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Rob Reiner, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

A few times you alluded to deleted scenes or killing your babies. If you were to talk to the young Bob that just bought his Laserdisc of the original Spinal Tap, thinking “how could they cut them out?” Now, you’re the guy that can explain why that happened.

When I was getting the dailies - between this film and the Albert Brooks documentary - I’ve never laughed so much in an editing room in my life.

When we were editing the documentary with Albert Brooks - it would be myself, Rob and Albert in the room – and I said, “If we put a camera in the editing room, we could release this as a sequel.”

There was a comedy show going on next to me every day between these two guys that have known each other since they were 16.

And Rob with the with the Spinal Tap guys - they’ve known each other for over 50 years, so there’s this dialogue they have that they’ve had for all these years. I would fall in love with scenes.

I would just laugh out loud and say, “Oh, this is in the movie!” I’d see a take and say, “Well, that’s in the movie!” or “That’s in the trailer. That says what the movie is.” So I would fall in love with these scenes. I’d cut them and think, “This is great.

Rob’s going to love this.” And he would say, “Get rid of it.” I would make my argument why I think it should be in there and Rob would sometimes say, “You’re right. Let’s leave it in there for now. That’ll set up something else.”

But what I’ve learned with Rob and other directors is that once they say “no” you don’t bring it up again because they’ve made their decision. You don’t keep harping on it. You don’t keep pushing. As an editor, you say, “I made my argument. I made my case.”

Within scenes that are in the film now there were what I thought were the greatest jokes in the world! But Rob or one of the guys would say, “We don’t like that joke.” And who am I to say? I can’t confirm or deny, but there might be some deleted scenes on the Blu-ray that comes out in the future, so you may see some of the babies I had to kill.

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

As someone who grew up watching deleted scenes and watching commentaries, it taught me a lot about what scenes were cut out. Why would they cut this? Then the editor or the director explained that it would screw something up later down the line.

In a film we did called LBJ there was a scene that we cut - one of my favorite scenes in the film - but by taking that scene out it connected the scene before it and the scene after it so perfectly. The transition between the two scenes was just too perfect, so a lot of times it’s just about the flow.

All the actors in this film had to be able to improv. If you have one actor in a scene that can’t do it, the scene just dies. So casting was very important.

The character of Simon was so funny and he was so good. At one point though, we thought, “It’s way too Simon- heavy,” so we had to kind of balance the movie. It’s a lot about balancing the characters, because you can fall in love with someone who’s just so good.

Something that I suggested - and Rob was totally on board with - was emulating the end credits of the original film.

If you remember the original film, the end credits are not outtakes, but are lines or funny bits. Some of the funniest stuff in the original film is in the end credits. We would save those. It’s not bloopers, it’s just additional material that didn’t fit anywhere else.

We created a bin that was just for end credits, so when the time came to do the end credits, I had so much material. Every scene is in the movie that they shot, so it was more about lines of dialogue or bits that I fell in love with that we had to get rid of because it just didn’t push the story forward.

It would go off in a different direction from the scene and you would say, “This is perfect for either the ending or the deleted scenes.”

My first cut of the movie was probably three hours, and it could have been longer because I was already sort of cutting in my head. Rob said the first cut of the original film was 5.5 hours, which is just insane. He got it down to about 83 minutes. The original film feels like the perfect running time. You don’t feel like you’re missing anything.

Christopher Guest, Rob Reiner in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

Did you always know that you were going to start at the end? Or did that structure happen in editorial?

That was planned because of the introduction by Marty DiBergi, which is a parallel to the original film where the film begins with him explaining that this is a reunion concert. I think that’s it just sets everything up. There’s a great dissolve from the full concert with the full crowd to an empty auditorium. That was planned because it had to be a lock off.

There are some shots of the guys backstage looking very nervous before this show, and that was something I added. I thought, “Well, this might be nice to show those looks on their faces.”

When we did a few test screenings, just seeing them in their stage make with their eyeliner on, you get laughter just seeing them sitting there. So you realize, “We’re in good shape here if they’re laughing just looking at them.”

Also, at a certain point you don’t think anything’s funny. Especially with comedies test screenings are really helpful because it reminds you when people are laughing. We had great responses at the coupleof test screenings we did, and we didn’t change that much.

We just sort of we realized people are really enjoying this. With comedies and horror films - where the whole theater jumps at a jump scare. Or with comedies where laughter is contagious. Rob said, “This is playing so well with an audience.”

That was why Rob and Bleecker Street really pushed to get a theatrical release. It plays so well with an audience. It’s just so much fun.

I personally miss that when you watch a comedy at home. You kind of chuckle to yourself, but with an audience you’re reminded: this is how we used to watch movies.

Seeing it for the first time with an audience justified what we had done by seeing people react the way we hoped they react.

The only thing we really changed was you would get such a big laugh from a particular joke that they would miss the next line of dialog that might be setting up something you needed, so you would have to build in those little, little beats.

Christopher Guest, Michael McKean, Harry Shearer in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

Rob says this about the first film that “This one goes to 11” was just another line in the film. You never know what’s going to become part of the lexicon.

So there were lines that we thought were just a funny line, but when we did the test screening they got a huge laugh. But then they missed the next 30 seconds of the following scene.

How did you deal with note-taking where you needed to open things up a little bit? Or did you record the test screenings?

I had never experienced a screening where they shoot the audience reacting. They send you a QuickTime, we bring it in, we sync it up to the picture, and it’s almost like a picture-in-picture.

You can actually see what they’re laughing at, what they’re not laughing at, what the biggest laughs are. It was very cool to be able to do that. Rob knows exactly - from sitting in the back of the theater – what to do. Immediately after the screening, he pulled me aside, and sais, “We gotta do this, this, and this.”

He doesn’t even need to see that video of the audience. But for me it was helpful to be very specific about what to adjust and how much. It’s a good problem to have to have too big of a laugh. It was very helpful to have the audio.

Was there any specific scene that you remember that was difficult to get down to time?

Probably the hardest scene was the scene with Paul McCartney because we’re all sort of in awe of him. That’s an example of a scene where if I could show you the 45 minute version, we could release that right now as its own film.

You think real life people - rock stars playing themselves - you expect them not to be actors, then suddenly you realize he’s been acting in movies for quite a while! Hard Day’s Night and things like that. He’s so good and he could improv with the guys perfectly.

That was a scene where you wanted to show the whole thing, but now we have to get down to the nitty gritty and compress that as much as possible.

It was hard because there was so much good stuff. You love seeing them interact with each other.

So that was probably the hardest scene. But I’m happy to say it’s still one of the longest scenes in the movie because it’s so good and there was so much material.

He was just a pro in terms of being just another actor in the scene. That was great because everything he did was perfect. Rob said, “You’re really good!” He said, “I’ve done some things before.”

“This is not my first rodeo!”

A lot of times you have to cut scenes with non-actors and I kind of worried, “How are Paul and Elton going to work?” But they just jumped in there with the guys who’ve been doing this forever. He was right up there with them.

Christopher Guest and Rob Reiner in Bleeker Street’s Spinal Tap II credit: Bleecker Street/Kyle Kaplan

I loved McCartney in the interviews. He’s clearly himself, but he had to perform a fictional situation.

The whole thing about his suggestions not being taken… He’s trying to help them with a song and they’re not listening to him! It’s crazy! That was somewhat based on a real situation years ago where somebody was recording an album and Paul stopped by to say hello.

It sort of came from that. Wouldn’t it be funny if Paul starts giving them notes and they don’t want to take his notes? There’s a great line in the movie where Paul says, “Well, it’s not my place to say…” And Nigel says, “Actually, it kind of is.” Paul was so good, especially when he was saying how much he loves this fictional band.

In these scenes where Rob’s interviewing the guys, they don’t know the questions he’s going to ask and he really doesn’t know the answers. So Paul didn’t know what Rob was going to ask him, so he could play along.

The sequel does have these people like Elton John, Paul McCartney or Garth Brooks. Since the original film came out it’s been this weird thing where real bands over the years have performed together with Spinal Tap.

They performed at Royal Albert Hall and in Wembley Stadium. They’ve sort of become this real band

Did you watch any mockumentaries or music documentaries?

I rewatched The Last Waltz. I wanted to see how they got in and out of scenes, because they’re building to this reunion concert that they’re being forced to do because of a contractual obligation.

I wanted to see - especially that film - how they intercut the interviews with the music and whether it was pre-laps as someone’s talking, then you get into the song or is it a hard cut or something like that.

The other thing was you really had to imagine the first film: Marty DiBergi made the original in 16mm in the style of documentaries at that time, whereas now most of them are streaming and they have a very specific style and outlook.

So there was that discussion amongst Rob and the director of photography: what would Marty DeBergi shoot this on? He wouldn’t shoot it on film.

I wanted to add film look to kind of emulate the original film but then you realize that Marty DeBergi would probably shoot it on an iPhone.

You had to take into consideration the current style of documentary cutting versus a 70s/80s editing. Now it’s very glossy. So we kind of took a little from both.

What would this look like if Marty DeBergi was making a documentary for today’s audiences? Versus making it look exactly like the first Spinal Tap, which I’m very happy about.

A lot of legacy sequels sort of just copy the first film. I like that this isn’t just a total rehash of the of the first film. I think it’s a great bookend to the original film.

You mentioned pre-lapping. One of the things that I noticed in the Elton John segment that they’re rehearsing, was that you start to hear his interview, even though you’re looking at him playing. Then cut to him being interviewed.

I like to do that, and Rob likes that too. It just keeps the flow. Not a lot of dead air. You want to see as much of Elton John playing. I’d rather hear him talking and see him playing as B-roll, as opposed to just staying on him. In that case, that sort of influenced the pre-lapping of that - just wanting to show as much of Elton John as you could.

You want to see this guy playing piano and you want to see the guys playing with him. The other way I guess would have been to just play the whole song all the way through and then go to the interview. You never want to bore the audience.

You want to keep it moving. As with the drumming sequence, how do we cut out the middle of the song a bit rather than play the whole song? We heard the band rehearsing “Listen to the Flower People” earlier by themselves, and then Elton does it with them, so you didn’t want to repeat the song again.

It was probably the hardest film I’ve ever had to cut just because of the nature of the film, which was completely a new experience.

I think I learned a lot from doing that for future films, too, because more than anything I learned from Rob is: don’t bore the audience.

Keep the movie moving. If it doesn’t tell the story - if it’s a scene that’s just there because you like it - you can lose it. It was just such a pleasure to work with Rob and the Spinal Tap guys.

Great words of wisdom to end on. Bob, thank you so much for your time, and congratulations on a great movie.

Thanks so much. I really appreciate it. Also, before I go, I want to thank my assistant editors: First Assistant Editor, Johnnie Martinez and Second Assistant Editor, Alex VanHeisch.

Joyce’s dog, Higgins, loyal editing mascot, who edited with Rob and Bob for the last five films.